Scientific Literacy: Your Secret Weapon Against Fitness Myths and Bad Health Advice

The fitness world can feel like the Wild West. One influencer swears that fasting is the only way to get lean. Another promotes an “ancient” exercise that will supposedly give you a shredded core in three days. Meanwhile, your friend just bought a fat-burning tea because someone on TikTok promised it was “doctor approved.” If you want to navigate this chaos without wasting your time, money, or health, you need one thing above all else: scientific literacy (OECD, 2017; UNESCO, 2017). By André Pedro

This article is not intended to provide a complete or exhaustive education in scientific literacy, health science, or fitness research methods. Its purpose is to raise awareness of the topic, highlight common pitfalls, and encourage readers to think more critically about the information they encounter. For comprehensive education, readers should consult formal courses, scientific texts, or professional training programs.

What is Scientific Literacy and Why Should You Care

Scientific literacy is not about memorizing the periodic table or wearing a lab coat. According to the OECD, UNESCO, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, it is the ability to understand how science works, to evaluate evidence, and to apply it to real-world decisions (AAAS, 2001; Guerrero & Sjöström, 2025).

It involves skills like understanding the scientific method, interpreting statistics, and spotting the difference between correlation and causation (Gal, 2002).

Real-Life Example: You see a headline saying “Scientists find coffee drinkers live longer.” A scientifically literate person checks if the study accounted for other factors like exercise habits, smoking rates, or diet before assuming coffee is a magic life extender.

Why It Matters in Everyday Life and in the Gym

Scientific literacy has been linked to better decision-making, healthier lifestyle choices, and even more active participation in civic life (Lee et al., 2011). People with higher scientific literacy are better at assessing risks, more resistant to misinformation, and less likely to waste resources on ineffective or unsafe products (Chou et al., 2018).

Real-Life Example: Instead of buying an expensive “metabolism booster” pill because the label says “clinically proven,” you look for the actual study, discover it was done on mice, and decide to keep your money.

How It Empowers You

When you are scientifically literate, you can spot misinformation before it costs you time or money (Chou et al., 2018). You understand that having visible abs does not necessarily mean a person is healthy (Lavie et al., 2015).

Real-Life Example: Your friend tries a “4-week shredded” program and loses 10 pounds. You try the exact same program and lose only 2. Instead of thinking you failed, you know about individual variability and adjust based on your own progress.

The Science Problem in the Fitness Industry

Misinformation spreads quickly in the fitness world. Studies have found that more than half of fitness content on Instagram contains unverified or misleading claims (Côté et al., 2020). Many people still believe that appearance alone equals health, despite strong evidence to the contrary.

Real-Life Example: A ripped influencer says they never do cardio, so you stop doing it too. Months later, you realize your endurance has dropped and your blood pressure has gone up – proof that looking fit isn’t the same as being healthy.

Correlation vs Causation, The Love Story That Isn’t

One of the most common ways people misuse science is by confusing correlation with causation. Correlation means two things happen together. Causation means one actually causes the other (Ioannidis, 2018).

Real-Life Example: You read “People who do yoga sleep better.” A closer look shows that many of these yoga practitioners also meditate, avoid caffeine late in the day, and have set bedtimes. The yoga might help, but it is not the only factor.

Scientific Studies, Which Ones Deserve Your Trust

Not all research is equally reliable. At the top of the evidence pyramid are systematic reviews and meta-analyses, which combine results from multiple high-quality studies (Guyatt et al., 2011). Even high-level studies can have flaws like small samples, short durations, or conflicts of interest (Lundh et al., 2017).

Real-Life Example: A company claims their protein powder “increases muscle growth by 50%.” You find the study and see it lasted only two weeks, tested just 10 people, and was funded by the company selling the powder. That is not enough to trust.

Practicing Scientific Literacy in Everyday Fitness Decisions

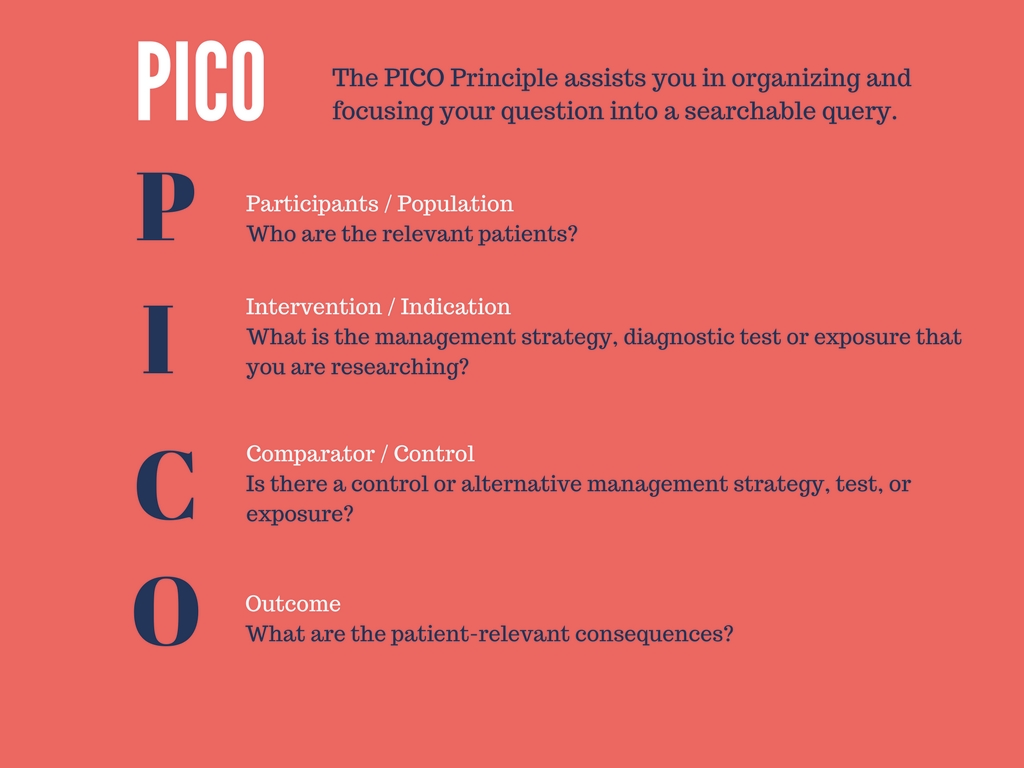

You do not need to be a scientist to practice scientific literacy. Start by asking for evidence every time you hear a claim. Read summaries from reputable sources (Shulman et al., 2020). Learn to spot misinformation tactics (Lewandowsky et al., 2020). Use PICO to break down studies (Richardson et al., 1995).

Real-Life Example: Before trying blood flow restriction training, you look up systematic reviews, see that it is effective for certain populations but not all, and then test it on yourself while tracking results.

The Bottom Line

Scientific literacy is not just for academics. It is a life skill, a filter against hype, and a compass for navigating the crowded and often misleading health and fitness marketplace. In a world where misinformation spreads faster than truth, scientific literacy is your most reliable training partner.

If you are curious and want to dig into the science yourself, here are five reliable places to start. These are credible, accessible, and written in a way that makes sense without needing a PhD.

- PubMed: The world’s largest biomedical research database. Use filters for “Systematic Reviews” or “Meta-Analyses” to get the strongest evidence. (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- Examine.com: Independent, evidence-based summaries of supplements and nutrition. Great for cutting through marketing claims. (https://examine.com)

- Cochrane Library: Gold-standard systematic reviews. Free plain-language summaries explain what the science actually shows. (https://www.cochranelibrary.com)

- American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM): Official position stands and practical exercise guidelines, backed by the world’s leading sports science body. (https://www.acsm.org/education-resources/position-stands)

- NIH Office of Dietary Supplements (NIH ODS): Clear, government-backed fact sheets on vitamins, minerals, and supplements. Unbiased and easy to read. (https://ods.od.nih.gov)

References

- AAAS. (2001). Atlas of science literacy. Washington, DC: American Association for the Advancement of Science.

- Bouchard, C., Blair, S. N., & Church, T. S. (2012). Adverse metabolic response to regular exercise: Is it a rare or common occurrence? PLOS ONE, 7(5), e37887. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0037887

- Chou, W. Y. S., Oh, A., & Klein, W. M. P. (2018). Addressing health-related misinformation on social media. JAMA, 320(23), 2417–2418. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.16865

- Côté, J., et al. (2020). An analysis of health and fitness information on Instagram: Misinformation and public health. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(10), e18938. https://doi.org/10.2196/18938

- Gal, I. (2002). Adults’ statistical literacy: Meanings, components, responsibilities. International Statistical Review, 70(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-5823.2002.tb00336.x

- Guerrero, G., & Sjöström, J. (2025). Critical scientific and environmental literacies: A systematic and critical review. Studies in Science Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057267.2024.2344988

- Guyatt, G., Rennie, D., Meade, M. O., & Cook, D. J. (2011). Users’ guides to the medical literature: A manual for evidence-based clinical practice. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Holbrook, J., & Rannikmae, M. (2007). The nature of science education for enhancing scientific literacy. International Journal of Science Education, 29(11), 1347–1362. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690601007549

- Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2018). The challenge of reforming nutritional epidemiologic research. JAMA, 320(10), 969–970. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.11025

- Lavie, C., De Schutter, A. & Milani, R. Healthy obese versus unhealthy lean: the obesity paradox. Nat Rev Endocrinol 11, 55–62 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2014.165

- Lee, H., Choi, K., Kim, S. W., & Krajcik, J. (2011). Re‐conceptualization of scientific literacy in South Korea for the 21st century. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 48(6), 670–697. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20424

- Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., & Cook, J. (2020). Beyond misinformation: Understanding and coping with the “post-truth” era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6(4), 353–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2017.07.008

- Lundh, A., Lexchin, J., Mintzes, B., Schroll, J. B., & Bero, L. (2017). Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2), MR000033. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.MR000033.pub3

- Melton, D. I., et al. (2010). Integrating evidence-based practice into fitness certification programs. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 32(6), 56–63. https://doi.org/10.1519/SSC.0b013e3181f5f7a4

- Nutbeam, D. (2008). The evolving concept of health literacy. Social Science & Medicine, 67(12), 2072–2078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.050

- OECD. (2017). PISA 2015 assessment and analytical framework: Science, reading, mathematic and financial literacy. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264281820-en

- Richardson, W. S., Wilson, M. C., Nishikawa, J., & Hayward, R. S. (1995). The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions. ACP Journal Club, 123(3), A12–A13. https://doi.org/10.7326/ACPJC-1995-123-3-A12

- Shulman, H. C., Dixon, G. N., Bullock, O. M., & Colón Amill, D. (2020). The effects of jargon on processing fluency, self-perceptions, and scientific engagement. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 39(5–6), 579–597. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X20902177

- UNESCO. (2017). Science education for sustainable development: UNESCO guidelines. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

Challenge of the Month

What Clients Say